Mission: Implausible, Pt. I -- The Playboy (S6E4)

- Gavin Whitehead

- Nov 30, 2025

- 20 min read

Born in Egypt to German parents, Johannes Eppler agreed to spy for the Nazis sometime around 1940. In 1942, he embarked on a mission to enter Egypt by way of the perilous Western Desert so he could gather intelligence for the German military.

This episode is currently available exclusively to patrons of The Art of Crime. If you'd like to listen now, please consider beocming a patron at www.patreon.com/artofcrimepodcast.

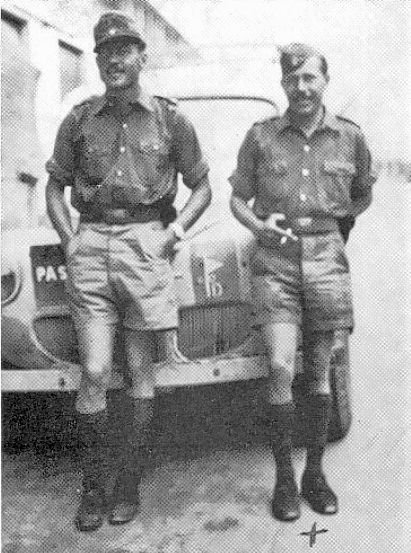

Above; Johannes Eppler and his sidekick, "Sandy."

SHOW NOTES

Undated photograph of Johannes Eppler with his stepfather, mother, and half-brother. The apple of his step-daddy’s eye, Eppler converted to Islam and changed his name to Hussein Gaffer. His German mother remained Catholic. Throughout his life, Eppler felt torn between the Egyptian and German facets of his identity.

In 1942, explorer László Almásy probably knew the Western Desert better than any other living European. He was a natural choice to lead the absurdly dangerous “Operation SALAM.” Almásy’s quixotic search for the fabled oasis city of Zerzura did not bring him riches. But it did lead to several real geographic discoveries, including caves with prehistoric art. In this undated photograph Almásy sketches some of the wall painting he has observed in the field.

British Light Tanks, Crossing the Western Desert. Taken in 1940, this photograph foreshadowed the upcoming battle for the desolate terrain separating Egypt from Libya. It was this high-stakes struggle that brought Eppler back to Egypt. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum (Photograph E 443).

Cairo was Eppler’s favorite city. During his time abroad training as a spy, he missed the incomparable vitality of its street life. An enthusiast of high and low culture alike, Eppler was as comfortable in an exclusive nightclub as he was among working-class settings. This picture, taken in the late 1930s, depicts an itinerant street barber, one of many Cairo’s outdoor sights that struck European visitors as exotic. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

TRANSCRIPT

Asmahan was not the only Egyptian entertainer to engage in espionage during the Second World War. And, unlike Asmahan, some Cairo-based artists did not yearn for an Allied victory. This three-part miniseries tells the story of Operation Condor, an ill-fated espionage campaign that unfolded in Cairo during the Nazi effort to capture Egypt’s capital via the Western Desert. At the center of the story are two very unlikely spies: an Egyptian-born German playboy and the Arab world’s most famous belly dancer.

Today, we’ll hear how the playboy, Johannes Eppler, was converted to the Nazi cause, how he undertook a hazardous journey by land across the Western Desert, and how Hekmet Fahmy—Egypt’s most celebrated dancer—became his most valuable intelligence asset. This is The Art of Crime, and I’m your host Gavin Whitehead. Welcome to Part 1 of Mission Implausible : “The Playboy”.

A Double Life

Johannes Eppler was not your typical Nazi spy. Also known as “Hans” or sometimes even “John,” he was born in 1914, in Egypt, to German parents. His Bavarian mother, Johanna, ran a modest, yet comfortable, hotel in the sun-soaked coastal city of Alexandria. Johannes’s father, a German businessman, frequently traveled to Europe for work, leaving his wife alone. Though lonely during her husband’s absences, Johanna took comfort in her son—and in the companionship of one of the hotel’s long-term guests: Saleh Gaffer. Gaffer was an affluent Egyptian judge who lived in Cairo; during his regular stays in Alexandria, he made the Epplers’ hotel his second home. Solicitous, respectful, and urbane, the jurist befriended the entire family and became Johanna’s close confidant.

In a shocking reversal of fortune, Mr. Eppler died when Johannes was still a child. After a suitable period of mourning, Johanna married Saleh Gaffer, who adopted her German son as his own. Gaffer showered Johannes with gifts and introduced his new wife to Cairo’s elite social scene, where she was admired by all for her wit and charm. Within a few years, the couple had another son, Hassan. Though Saleh was a kind and attentive father to both boys, he had a special fondness for Johannes, whom he still considered his first-born child. By all accounts, they were a happy, well-adjusted family.

Even so, young Johannes felt torn between the German culture represented by his birth parents and the values associated with his upbringing as an Egyptian daddy's boy. At Saleh’s urging, Eppler converted to Islam and spoke Arabic at home. He was also given a new name: Hussein Gaffer. His mother, meanwhile, secretly instructed him in the Catholic faith. He also attended a European-run school, where he studied in French and German. Thus, at an early age, Johannes lived a kind of double life, existing at the cross-roads of two cultures, without fully sharing the social or religious beliefs of either one. In his memoirs, he recalls suppressing his spiritual doubts to please his parents, particularly his doting stepfather: “I continually felt the need to dissemble and the result was an attitude of estrangement, which made me feel insecure. I was having to struggle with pangs of conscience.” In donning this cloak of perpetual secrecy and dissimulation, Eppler took the first step toward a career as a spy.

In his teenage years, Hussein—for the sake of simplicity, we’ll call him “Johannes”-- developed two other personality traits that nudged him a little closer toward the field of espionage. The first was a love of adventure, which he traces back to his youthful pilgrimage to Mecca, in which he traveled overland through the desert with his Bedouin uncle. Coming from a rich family, he also flirted with aviation, an expensive hobby undertaken by many wealthy Egyptian males. Second, during his adolescence, Eppler discovered his love of social life, particularly of the jet-set, European variety. Unburdened by the threat of poverty, the future Johannes would not have to work for a living. So, rather than toiling away in the library or preparing for a career, he spent most of his time hanging around Cairo’s best sports clubs, coffee houses, and cabarets. He also enjoyed frequent—alcohol-fueled—excursions to seaside resorts throughout the Middle East. It was during one such trip that the Nazis made their first overture toward the rudderless youth.

The Seduction

In August of 1938, the world was steadily edging toward outright war. By contrast, Hussein Gaffer was kicking it in Beirut, at the swanky St. Georges Hotel, no worries in sight. Built in 1934, the St. Georges exuded modern luxury. Its façade—dominated by straight, functional lines—looked out onto the sea. Catering to well-heeled travelers from across the globe, the establishment was the haunt of many spies, drawn to its well-appointed bar and ballroom like cats to a laser pointer.

Now age 24, Johannes measured 5’3”. Slim, athletic, dark-haired, and tastefully mustachioed, he could pass as Egyptian or European. His lively, dark eyes and good humor won him friends wherever he went. Even so, he had spent most of his stay in Beirut swimming in the sea by himself, stealing furtive glances at the hotel’s more attractive European guests. One woman, in particular, caught his eye. In one version of the story she’s Hungarian; in another, Vietnamese. Whatever the case, his first tentative efforts to attract her attention fell humiliatingly flat. Then, his luck turned around one evening, while he was nursing his whiskey soda alone at the bar. To his astonishment, the beautiful woman approached him, introduced herself, and asked him to dance. One thing led to another, and the next thing Johannes knew, his love interest was introducing him to her “friends”—a pair of blonde-haired, blue-eyed women who just so happened to be spies for the Abwehr—Hitler’s military intelligence unit. As luck would have it, the Abwehr was on the prowl for fresh talent, and they were not above using the honeypot technique to snag new recruits. Johannes had been catfished, Nazi style.

What happened next altered Eppler’s sense of self. With the outbreak of world war seeming more probable with each passing month, he hadn’t thought much about what such a conflict might mean for him. So far, Egypt had struck a neutral position in the growing tensions among the major European powers. Eppler, who saw himself as an Egyptian citizen, didn't really care, one way or the other. However, events in his own household foreshadowed the internal struggle that he was about to confront as a result of global politics. His stepfather, an ardent Anglophile, full-throatedly supported the UK's cause. Johanna, on the other hand, began paying a little too much attention to Nazi radio broadcasts coming out of Germany. Eppler averted his gaze as his mother covertly consumed political ideas that were anathema to his stepfather.

Eppler’s Nazi spy recruiters appealed to his memories of Germany, which he had visited several times as a youth. They also flattered Eppler. Didn’t he realize that his experience growing up in Egypt gave him knowledge and skills that were uniquely useful to the German cause? Didn’t he realize that they had picked him out explicitly for his potential as an agent in the Middle East? They didn’t recruit just anyone, you know—only German patriots of exceptional talent and potential. Johannes, who spent most of his adult life drifting from one party or resort to another, immediately felt a sense of purpose at the thought of aiding the revitalization of Germany. What is more, he sensed the potential for great adventure, for a sense of purpose that he currently lacked. As he would repeatedly remark to his German handlers: He didn’t need a salary; adventure was its own reward.

Over the next year, Eppler undertook various minor errands for the Abwehr throughout the Middle East. Having succeeded in these little quests, he was ready to become a full-fledged Nazi spy. When he returned to Egypt, he laid the groundwork for the next phase of his life, which entailed leaving behind his past in order to undergo the covert training that would qualify him for the dangers of spy craft.

Berlin

In 1941, Eppler reported to Berlin, where he abandoned the name given to him by his beloved stepfather. As Johannes Eppler, he signed an affidavit that, despite his Egyptian upbringing, he was, to the best of his knowledge, of 100% Arian stock. Though initially motivated by romantic, postcard images of German civilization—Goethe, the Rhein, Lederhosen—Johannes quickly looked askance at the Nazis, who vowed to restore its lost greatness. He was surprised to note the boorishness of many of the parties’ leaders, including Hitler.

On top of that, as part of his training, he entered an accelerated military academy, which harshed his laidback, playboy vibe. While he excelled at everything having to do with cryptography, cartography, and signals intelligence, he bungled a lot of the physical tasks. The longsuffering officer who tried—in vain—to teach Johannes skydiving finally threw up his hands air in resignation, exclaiming: ““You landed like a potato sack falling out of the sky, Sir. If you ever have to make a real jump and you break every bone in your body when you land, don’t imagine there will be anyone waiting to help you stick them together!” More problematic still from the perspective of his handlers, Eppler mocked the rigid, self-serious hierarchy that structured all aspects of Nazi life. Upon witnessing his mentor grovel before a superior officer, Johannes quipped: “We [Egyptians] wouldn’t speak to Allah as abjectly as that. Herr Lieutenant here, Herr Lieutenant there, everything in the third person. You’re all out of your minds!” When he showed up at military complex for training in tank warfare, he addressed the guard in a shockingly nonchalant way. This led to him being mistaken as a foreign spy and detained until his identity could be verified.

In modern corporate speak, then, the marriage between Eppler and the Nazis was not exactly a good “culture fit.” Under normal circumstances, Johannes probably would have been discarded as a hopeless case. However, by 1941, the Middle East began to assume a more prominent role in Germany’s plans for global domination. The Abwehr was desperate for agents who could blend into Arabic-speaking countries, who understood Muslim cultural norms, and who had the necessary mixture of social grace and daring. While Eppler was a cutup who couldn’t parachute and who would never fit in around party quarters in Berlin, as a field agent, he would surely shine. -–Or, so his handlers was hoped. After a series of relatively inconsequential assignments, Eppler finally got his big break the following year—a dramatic mission that would return him to his native Egypt, this time, as a spy.

Call to Action

In June of 1940, Italy invaded Egypt from their colonial stronghold of Libya, only to get routed by Allied forces. Mussolini, licking his wounds, went hat in hand to Hitler, begging for assistance. This was far from Hitler’s top priority, but he was eventually convinced to send General Field Marshall Erwin Rommel to oversee another attack on Egypt via the Western Desert, the inhospitable wasteland that separated Egypt from Libya. Rommel vowed to drive the U.K. and their allies out of Egypt, which—though nominally independent since 1922—was still, in effect, under British control. Rommel daydreamed of Nazi flags clotting the streets of downtown Cairo—and being raised aloft over the Pyramids. In Winter of 1941, the German Field Marshall began preparing an aggressive military campaign to attack the major population centers of Alexandria and Cairo via the vast and deadly Western Desert. Over the centuries, Egypt had had a precession of conquerors, but none of them had successfully taken the country from the west.

In addition to the geographical challenge ahead of him, Rommel had to contend with a second obstacle. The Nazis had no quality intelligence coming out of Egypt. In particular, Rommel desperately needed a spy who could extract information from British officers stationed in Cairo—the military headquarters of the U.K.’s Middle Eastern operations—and radio it to him in the Western Desert.

Back in Berlin, the Abwehr poured over its assets and happened upon an obscure Egyptian-born spy who spoke Arabic like a native and was intimately acquainted with Cairo. They summoned Eppler to headquarters and outlined their plans to infiltrate a spy into Cairo, a mission that they called “Operation Condor”—and in which he would play the starring role.

Never one to obey in silence, Johannes instantly raised two objections: First, he scoffed at the Nazi’s plan to manufacture a fake Arabic name for him. Eppler insisted that it made far more sense for him to return to Egypt as “Hussein Gaffer.” In the first place, lots of Cairenes knew him by that name, and it would look suspicious to go parading around the city under another one. What is more, the Gaffers were a highly respected family. The name opened doors. Then, there was the fact that his stepfather, Saleh Gaffer, was one of Cairo’s most vocal Anglophiles; this made it highly unlikely that the British would investigate a member of the judge’s family. In the end, the spy got his way. If all went to plan, he would be returning to his beloved Cairo under the name given him by his overindulgent stepfather.

Second, Eppler refused to undertake the mission alone; he wanted a partner in Cairo. This wish was granted as well. Enter Heinrich Sandstette, whom Eppler nicknamed “Sandy.” Sandstette was born in Oldenburg, Germany in 1913 and had spent much of his life wandering Africa, where he learned English. Taller and less outgoing than Eppler, Sandy had actually met Johannes in Berlin during their training. The two men instantly got along. On this particular mission, Sandstette would serve as Johannes’s radio operator, a job that he knew well.

With Eppler’s qualms addressed, one last loose end remained. Unfortunately for the Abwehr, it was a daunting one. Ever since Mussolini’s first foray into the desert, security in Egypt had been heightened. Under more auspicious circumstances, the Nazis might have just parachuted this pair of spies into the countryside, where they would find their way to the Egyptian capital. However, Egypt overflowed with military checkpoints. Since parachuting was an obviously suspicious activity, there was little hope of entering the country by even these far-fetched means. However, if Sandy and Eppler could be flown to Italian-ruled Libya, they could drive through the desert using obscure and forgotten routes far away from the official roads patrolled by the British. They could then be dropped off outside a town in the Nile delta. If asked where they had come from, the duo would explain that their car had broken down in the desert and that they had walked in the direction of the closest known settlement.

This plan entailed a long, perilous trek across little-known terrain, without the benefit of water, gas stations, supermarkets, or reliable maps. On the face of it, the idea seemed deranged. However, the Abwehr had an ace up its sleeve. Already stationed in Libya was yet another human asset, whose eccentricity was rivaled only by his exceptional knowledge of Egypt’s western wasteland. He and a team of military assistants would convey Johannes and Sandy through the desert’s most obscure nooks and crannies, in a daring campaign that the Nazis dubbed “Operation SALAM.”

Operation SALAM

László Almásy was born in Bernstein, Austria in 1895. The son of a respected zoologist, Almásy styled himself as a Hungarian Count, though the title actually belonged to a different branch of his family. Having tried his hand at a number of boring bourgeois jobs, Almásy found his calling in 1926, on a road trip from Egypt to Sudan. A quarter of the way into 20th century, the spurious Count decided to live his life in a deeply Victorian manner: by becoming a geographical explorer of inland Africa.

More specifically, he resolved to know every inch of the sketchily-mapped desert between Libya and Egypt. Throughout the 1920s and 30s, Almásy embarked on a series of desert explorations, by automobile and airplane. These campaigns yielded genuine geographical discoveries. For instance, he was the first known European to visit the Cave of the Swimmers, a cavern in the Libyan desert that features prehistoric images of humans swimming.

However, he channeled most of his exploratory zeal toward the lifelong dream of finding the lost—and probably mythical—Zerzura Oasis. First mentioned in a 15th-century compendium of Egyptian folklore, Zerzura was thought to be a fabulously rich, whitewashed city in a remote region of the Sahara. Oral legends about the oasis were still current in Egypt in the 19th century, which is how Europeans first learned of the storied settlement. Almásy went on several collaborative expeditions to rediscover Zerzura. In the process, he amassed a vast—nearly encyclopedic—knowledge of the terrain of the Western Desert: its rock formations, its bandit-den caverns, its hidden thoroughfares. (If any of what I’ve just told you rings a bell, it’s probably because Almásy’s life was the VERY loose inspiration for the novel and film THE ENGLISH PATIENT.)

It was the Hungarian explorer’s experience in the Western Desert that qualified him to ferry Johannes and Sandy across the vast, arid region as leader of Operation SALAM. After months of careful planning, the men were ready to undertake the perilous mission on April 29, 1942. The spies, Almásy, and his assistants left from Tripoli in 8 cars, some of which were carrying the water, food, and gasoline necessary for the round trip. The first leg of the tour was easiest, taking them to Libya’s Jalo Oasis. From there, the convoy attempted to travel east, avoiding modern roads. The Italian-made maps that they had consulted suggested that there were stretches of hard-gravel trail that they could take. What they found instead were vast, impassible dunes. As Almásy was attempting to cope with this stressful setback, several of the men became seriously ill. Then, the axel of one of the vehicles broke, forcing them to abandon it where it sat. Given this flock of calamities, there was really no other choice but to return to Jalo Oasis and try a different route.

On May 10th, Almásy left Jalo for the second time with a downsized convoy of 8 men in 6 cars. He also binned the misleading Italian maps, opting instead to follow a path that he had blazed during a previous search for Zerzura. At first, the journey was uneventful. Almásy squirmed occasionally at the slovenliness of Eppler and Sandsette. In his diary, he refers to them as “the most untidy fellows I’ve ever had under me. The inside of the radio-car looks frightful – loads, personal effects, weapons and food all mixed up together.” Yet, far more serious annoyances were to come.

As they approached the so-called “Great Sand Sea,” the terrain got more challenging—and things got real. The drivers—inexperienced in desert travel—had to negotiate shifting sands and make their cars vault over dunes as tall as 200 feet, unable to see what awaited them on the other side. The days were scorching hot; at night, temperatures plummeted to 20 degrees Fahrenheit. Exhausted and in crippling pain, the convoy’s physician died of a disease known as “desert colic” on May 13th. A day later, one of the drivers was struck with a condition called—in the evocative vernacular of the period—"the galloping shits.”

There were calmer moments, as well. Along the way, Almásy took time out to stash barrels of water and gas in caverns and behind boulders, so that they would be there for his return trip. This allowed the group some downtime to sight-see. On May 18th, the convoy reached the Cave of the Swimmers, the Hungarian explorer offering his companions a tour of the site that he had uncovered nearly a decade earlier.

After this fascinating reprieve, adversity struck again. On May 21st, the convoy headed in the direction of Egypt’s Dakhla Oasis. Until this point, the men had used a portable wireless station to keep in daily contact with their command center, which updated them on any military developments in the desert. On this leg of the trip, they lost contact with this vital lifeline. This meant that the convoy could, at any time, bumble directly into enemy hands. Sandy and Eppler, unaccustomed to the blistering heat and bone-shaking driving conditions of the desert, became exhausted, prompting Almásy to dose them with heroic quantities of amphetamines. Everyone persevered as best they could until May 23rd, when they passed through the Kharga Oasis in Egypt. From there, it was just a short drive to the outskirts of the town of Asyut, situated on the west bank of the Nile, roughly halfway between Cairo to the North and Aswan to the South.

It was on the road going into Asyut that Almásy bid adieu to Eppler and Sandy. Operation SALAM had come to a successful end. Operation Condor was now underway.

First Steps

Standing alone on the dusty road into Asyut, Eppler and Sandy first had to make it into town and then find their way to Cairo. They double-checked their identity documents. Eppler, of course, was simply resuming his Egyptian life where he had left off, as Hussein Gaffer. As for Sandy, the Abwehr decided that, with his mid-Atlantic English accent, he would make a passable American; from this moment on, he assumed the name “Peter Monkaster”, proud Yankee and international traveler. Walking toward the city, the spies schlepped four suitcases, one containing their radio equipment, and another 50,000 British pounds in cash.

Approaching Asyut, they encountered their first challenge. They followed a sharp bend in the road, only to see a British military camp on the other side. Sandy sweat profusely. There were Allied troops everywhere, and if an official asked them to open their suitcases, they’d have a lot of explaining to do. Eppler wasn’t worried. He could B.S. his way through this. Then, a British major—clearly meaning business—approached them in the road. Who were they? And where the hell had they come from? There was nothing but desert for hundreds of miles. In answering the military officer, Eppler drew on his deep reservoirs of blarney and charm. Here are his own words, as reported in his memoir:

“I explained that our car was some way back behind the hill and that we had broken down. As we had managed to get this far, we should be grateful for a lift to the railway station, since we had to be in Cairo by the next day. I can still hear him asking in amazement. ‘To the station? I can’t do that without knowing who you are. We are not running a taxi service, you know.’

I immediately introduced Sandy, my American friend, who had wanted to see the desert before he returned to the States. Then, showing my passport as Hussein Gaafar, I let it drop that he had probably heard of my family in Cairo. The major seemed suitably pleased to meet us and suggested that we all go and have something to drink. After that, he would arrange for some transport to Asyut. It was a simple as that! We had some marvellously cool whisky and soda, served by a batman. There was some lively talk about the desert, which had after all been a topic of everyday conversation with us for the past three weeks and on which we were therefore pretty expert.”

And just like that, the British military personally escorted Nazi spies to the railway station. Sandy and Eppler purchased two tickets to Cairo. Prior to departure, there was still one last issue to resolve. The suspicious content of their suitcases would surely be turned out by British inspectors in Cairo's railway station when they arrived. But Eppler had an idea to get around this. Sitting by the train station was a group of Nubians chatting with each other. Eppler approached them and asked them in Arabic if any of them were seeking work. Before long, he had contracted the services of a 17-year-old boy named Mahmoud. Eppler promised the teenager 6 Egyptian pounds per month to work as his valet. The youth, eager to please, agreed to take the two spies’ suitcases to Cairo ahead of them. As Eppler explained to Sandy, the railway inspectors were not going to detain a simple Nubian lad from the countryside and investigate his luggage. Eppler entrusted their bags to Mahmoud. In that moment, Sandy’s chin nearly hit the dusty ground. Shocked, he upbraided Eppler for handing a total stranger £50,000 in cash, not to mention their long-range radio equipment. Eppler smiled. If Sandy had ever been to Egypt before, he would know that Nubians are the most honest people in the world. There was zero chance that Mahmoud would vanish with their belongings. And it turns out Eppler was right. When the two spies arrived in Cairo, Mahmoud was waiting for them in the specified spot, smiling, their unopened suitcases in hand.

The day after their arrival in the capital, Sandy and Eppler would have to begin searching for a house, which would serve as the home base for their radio transmissions to the Nazis. That evening, they would stay in a modest pension. Sandy, exhausted, assumed that everyone was going to hit the hay early and get a full night's sleep. Eppler had other plans. Here he was, back in his favorite city, a city of unrivaled energy and sensory stimulus. During his long absence, he had missed the indescribable buzz of his hometown. There was no way he was going to bed early.

He thought over his entertainment options. One struck him as the obvious place to spend his first night back in town: the Kit Kat Club. Located alongside the Nile, the Kit Kat was the hottest cabaret in town. That was enough reason to head in that general direction. However, Johannes also knew that, at the Kit Kat, he was sure to find an old friend and lover, who just so happened to be Egypt's most celebrated belly dancer.

Hekmet

Hekmet Fahmy was born in 1907, somewhere in Egypt. Not much is certain about her early life, including her birth city. During her youth, she dreamed of being an actress. With her dark hair, copper skin, and sparkling green eyes, Hekmet made an impression when she entered a room.

At some point, she moved to Cairo to pursue her showbiz dreams. She started by taking bit parts in various theaters in the Azebakeya District, the city’s epicenter for the performing arts. In the late 1920s, she got her breakout gig in the sala—or, music hall—of singer, actress, and belly dancer Badia Masabni, one of several female entrepreneurs who dominated Cairo’s thriving nightlife industry. (We mentioned Masabni’s burlesques of Hitler in our episode on Asmahan.) Under Badia’s wing, Hekmet would find her niche in showbusiness. Mastering Masabni’s belly dancing techniques, she soon innovated on them, eclipsing her teacher in the process. Movie roles followed, the first in 1933’s The Wedding, written and directed by Egyptian actress Fatma Rouchdi. In the 1930s, Hekmet also performed at the swanky sala of Mary Mansour—the same establishment that hired Asmahan to sing after her successful public debut at Cairo’s opera house. According to journalist Leonard Mosley, a big fan of her work, Hekmet elevated belly dancing to the level of serious art:

She put all her thoughts, her feelings, her ideas and her ambitions into every movement of her dance; and I hasten to say that they may have been emotional, but they were not always sexual. This was expressive dancing, and it excited, stimulated and aroused, and not necessarily merely below the belt of those who watched her.

When Eppler returned to Cairo in 1942, Hekmet Fahmy was no mere celebrity; she was an institution. Easily the highest paid dancer in the Arabic-speaking world, Hekmet was seen all over town with elite businessmen, artists, and politicians—not to mention high-ranking British military officers, who panted after her by the dozens. Fabulously wealthy, she opted to live in an opulent houseboat, stationed between the western bank of the Nile and Gezira Island, home to the Cairo’s fashionable Zamalek district. At this point in her life, Hekmet was the headliner at two of the city’s most exclusive entertainment venues: the Kit Kat Club and the rooftop bar of the very expensive Hotel Continental. Both establishments catered to wealthy Egyptians and, increasingly, to large numbers of Allied officers and soldiers.

On his first night back home, Eppler—a.k.a. Hussein Gaffer—wanted to see Hekmet Fahmy before anyone else and therefore went to the Kit Kat. Though Eppler’s memoir doesn’t furnish dates or many other particulars, it strongly implies that he and Hekmet had been lovers at some point in the past. But this wasn’t simply an opportunity to catch up on old times. As he watched the belly dancer interact with scores of leering British officers, he marveled at how much power she exercised over them. If anyone could get her finger on the pulse of Allied secrets, it was Hekmet.

When the Kit Kat closed shop for the night, Eppler accompanied Hekmet back to her houseboat, where a good time was had by all. During this interlude, Hekmet’s beloved Hussein sounded her out regarding her opinions of the British. To his surprise, she expressed intense hatred for them, born of a desire to see them driven out of Egypt. She explained that, in her line of work, she had to be nice to everyone, notwithstanding her fervent desire for national independence. Eppler, sensing an in, converted her over to the Nazi cause. She had no sympathy for Hitler’s aims but thought that the Nazis might end the British colonial presence in Egypt. This would turn out to be the smartest thing he did in Cairo. Within a matter of days, Hekmet found him a homebase in the city. Within weeks, she intercepted top-secret documents that could potentially tilt the struggle for the Western Desert in General Rommel’s favor.

Comments