Mission: Implausible, Pt. II -- The Race Against Time (S6E5)

- Gavin Whitehead

- Nov 30, 2025

- 16 min read

Updated: Dec 16, 2025

Having made it to Cairo and forged an alliance with belly dancer Hekmet Fahmy, Johannes Eppler began snooping around for intelligence that could be of use to the Nazis. It was thanks to Hekmet that the spies got their first--and only--break in the case.

Above: The Basilica of St Therese of the Child Jesus. Finished in 1932, this Catholic church was located in the Cairo suburb of Shubra (or Shoubra). It was here that Eppler met Father Demitrius, Nazi priest and spy. Photograph courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

SHOW NOTES

Cairo House Boat (or “dahabiha”). House boats became the abodes of the rich and fashionable of Cairo during the 1920s and were still preferred by the city’s Bohemian types into the 1940s. After World War 2, they lost their sheen. Even so, they became visual reminders of Egypt’s pre-war past—until recently, that is. In 2022, the government oversaw the removal and destruction of most of Cairo’s historic houseboats, to make room for new development. Photograph courtesy of the Flickr account “Sjonnie 2000”: https://www.flickr.com/photos/33757980@N00/.

Hekmet Fahmy was known for elevating belly dancing to a serious art form. After appearing in a string of movies, she cemented her reputation as Egypt’s most lauded belly dancer.

Fahmy began her career in a “sala”—or music hall—owned by Badia Masabni (depicted in the center). Masabni taught Hekmet how to dance. She was also one of several female entertainers/entrepreneurs who dominated Cairo’s art scene.

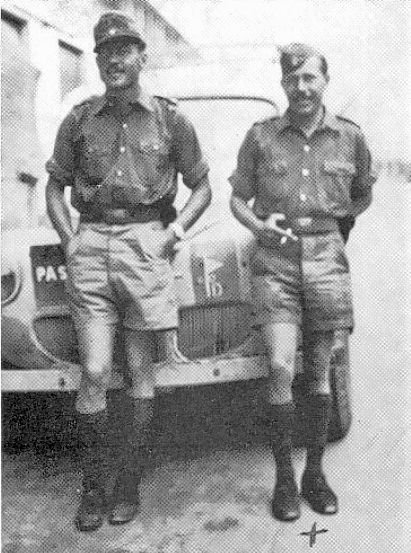

Eppler posing as a British soldier in Cairo. During the day, Eppler would drink at the Turf Club, where he attempted to gather information about British military movements. After his cover was blown by skeptical barfly, he retreated from the Turf and channeled his energies in other directions.

TRANSCRIPT

It’s June of 1942, and you’re an Australian soldier on leave in Cairo. You’ve come from Egypt’s Western Desert, where Allied forces are battling the army of Nazi General Erwin Rommel. Hitler is boasting that, within the month, he will capture Alexandria and then Cairo itself.

It’s your first night in the Egyptian capital, so you go where the action is: the Kit Kat Club. Opened in 1923, the Kit-Kat is the grand-daddy of Cairo’s celebrated open-air cabarets. Located right on the Nile, opposite the stylish neighborhood of Zamalek, the Club attracts a mixture of foreign tourists, affluent Egyptians, and Allied Officers.

Let’s also say you’re from a town where nothing much usually happens: Port Augusta—or, if you’re lucky—Adelaide. When you turn into the Kit Kat, you marvel at its entryway, an imposing marble replica of a triumphal arch, commemorating Napoleon’s victory at the Battle of the Pyramids. Once you walk into the cabaret proper, it’s sensory overload. In the enormous terrace, people from all over the world crowd around tables, drinking and dining under the stars and enjoying the cooling breezes coming off the Nile. The seating is carefully arranged to provide good sightlines to the elevated stage, which peaks above a raised platform that accommodates an entire orchestra.

You pass through a line of potted palm trees, toward a knot of British military officers, standing around and musing about the desert campaign, pounding scotch and gin. You take a seat in front of the stage. You’ve heard wonders about the establishment’s cabaret, which features singers, dancers, and dramatic acts. The curtain opens, and famous belly dancer Hekmet Fahmy takes to the stage. Since this is your first exposure to Cairo’s showbiz scene, you DON’T know that Fahmy used to work alongside superstar singer Asmahan, in the music hall of actress Mary Mansour.

But, in terms of the things you don’t know about this belly dancer, her CV is the least of your worries. Unbeknownst to just about everyone, Fahmy is exploiting her nightly gig at the Kit Kat to advance her latest side-hustle, as a Nazi spy.

On stage, she glances over to that group of British officers you noted earlier. Fahmy sets her sights on a lech with a roving eye and a high security clearance. If all goes as planned, she will shimmy her way into his heart and unburden him of the secret documents back in his office. She will then turn this information over to her part-time boyfriend, Hitler’s chief spy in Egypt, who’s sitting right next to you during Fahmy’s act, a stupid, leering smile spreading across his face. As is true of Cairo itself, nobody in the Kit Kat is quite who they seem.

This is The Art of Crime, and I’m your host, Gavin Whitehead. Welcome to Part 2 of our special holiday miniseries, Mission Implausible, “The Race Against Time.”

Time Crunch

The morning after his return to Cairo, Johannes Eppler woke up in the glamourous houseboat of friend and former lover Hekmet Fahmy. It was 6:00 in the morning and the rising sun drifted through the bedroom window and illuminated the white silk mosquito net that encircled Hekmet’s wide, sumptuous bed. Eppler got up and put on his clothes. He had a lot to do, and he needed to do it now.

In June of 1942, Axis troops, led by Rommel, were fighting the Allies in the Battle of Gazala, named after the Egyptian village where it unfolded. This skirmish would be the first of two upset victories for Rommel, who successfully pushed Allied troops back from the desert and closer to the Nile. In order to maintain this momentum, Axis forces had to take Alexandria before September, by which time reinforcements would arrive for the Allies. Rommel, therefore, urgently needed fresh intelligence from British headquarters in Cairo.

Eppler understood what this meant for him and Operation Condor. His bosses at the Abwehr, the Nazi’s bureau for military intelligence, had already explained the three things that Rommel most needed to know:

(1) Where in the Nile Delta are the British planning on making their last stand?

(2) What reinforcements are they counting on, and when?

(3) Who is going to lead those reinforcements?

In a matter of days, Eppler had to assemble a network that could help him ferret out this sensitive, top-secret information. At the same time, he must find a safe, secure homebase for his spy operation. Cairo was crawling with Allied officers and British counterintelligence assets. It was vital to locate a place where Eppler and his radio operator Sandy could transmit their intelligence to Rommel without being observed or traced.

Thus, on his first full day in Cairo, Eppler cracked his knuckles and got to work. Count Lázló Almásy, the Hungarian desert explorer who shepherded Eppler and Sandy across the western desert, had given him the name of a Nazi sympathizer, whom Eppler was supposed to contact once he arrived in the Egyptian capital. So, Johannes borrowed Hekmet’s car and drove to the Cairo suburb of Shubra. As far as subterranean Nazi contacts go, this was a highly unusual one: a Hungarian by the name of Father Pierre Demitrius. A Catholic priest, Father Demitrius could be found at the Basilica of St. Therese of the Child Jesus. The Nazi cleric had recently stopped transmitting his radio reports to Rommel. Eppler had to check in on him to find out why and ask for help in finding a location where it would be safe to send his own wireless telegraphs to the Abwehr.

Johannes st00d outside and looked at St. Therese. Built in the 1930s, it was a relatively new church, its façade adorned with multi-colored pastel tiles, arranged in beautiful geometric patterns. Though his mother, who never converted to Islam, was a devout Catholic, Eppler didn’t really feel at home in churches, so took a deep breath as he crossed the threshold.

The basilica was dark on the inside. Scattered thinly across the pews were tufts of pious elderly women. Their gazes were trained on the tall, gaunt priest standing in front of the altar. There was something magnetic about him. With dark, glistening eyes and a shock of unwieldy white hair, he commanded even Eppler’s attention as he intoned the mass in Latin. Johannes, playing the tourist, examined the side chapels until the service was over. Almásy hadn’t told him what the Hungarian contact looked like. Was this old, and strangely hot, priest the right man?

There was only one way to know for sure. Eppler and the Nazi cleric were both given secret Latin passwords to identify each other. As the priest approached the vestry, Eppler intercepted him, looked him straight in the eye, and uttered the phrase: “Alma mater”—meaning “nurturing mother.” The priest’s deeply lined face enlivened in recognition as he replied “Cor ad cor loquitur”—“Heart speaks to heart.” The Nazi agents exchanged a meaningful look; Eppler had found his Father Demetrius.

The priest ushered the spy into the vestry. Demetrius told Eppler about the secret radio that he had installed near the altar of the church. He also explained why he had stopped transmitting messages to Rommel: British counterintelligence agents were currently scouring Cairo for Nazi abettors in the wake of a botched mission on the part of the Abwehr. At the same time, Demetrius suggested that it was safe for Johannes to use the basilica as the base for his own transmissions. Though little known for his piety, Eppler—in contrast the priest—balked at the idea of using a church to transact Nazi business. It was bad luck and, perhaps more importantly, in bad taste. After exchanging a few more words with the Father, he hurried out of the basilica. The visit had failed to furnish any interesting intelligence and did not get Eppler any closer to securing a homebase in the city. Lucky for him, across town, Hekmet Fahmy was working her special brand of magic.

The Boat

As Eppler wasted his time in Shubra, Hekmet was pounding the pavement, searching for a crib for the two spies. Then, she remembered was a vacant house boat—or, dahabiha in Egyptian Arabic—for rent, not far from where she lived. In addition to being close to Hekmet, the ship had another obvious advantage: It was located next door to a dahabiha that housed a Major in the British intelligence services. Hekmet knew him well. She nearly rubbed her hands together in glee: Who would ever think that Nazi spies would be brazen—or stupid—enough to live voluntarily next to such a neighbor?

Hekmet looked over the houseboat with satisfaction. It had everything a pair of spies could ask for. On its upper level, the dahabiha boasted an attractive sundeck with a long mahogany bar, stocked with every known liquor. Here, Hekmet could help Sandy and Eppler organize parties that would bring together beautiful young women and loose-lipped British officers. Below deck, the staterooms were stuffed with lavishly carved furniture and brightly colored textiles, resembling a harem scene from an Orientalist painting. Hekmet confirmed the rental price with the landlady—an eye-watering 12 Egyptian pounds per month, roughly 4 times the price of the average Cairo apartment. The dancer asked the owner to reserve the boat for her friends, who would come to sign the lease later that afternoon. For their part, Johannes and Sandy were delighted with the find. Eppler signed the lease under the name “Hussein Gaffer”—the name given him by his Egyptian stepfather and the one that he had adopted for Operation Condor.

As planned, Hekmet started inviting all the British military personnel and all the attractive young women she knew to the nearly nightly shindigs hosted by the two spies. There, Eppler and Sandy made friends among the Allied forces, including their security-officer neighbor, who became a regular on their houseboat.

Meanwhile, Sandy got to work installing his transmitter. He and Eppler were fortunate to have a combination radio and record player built into their deck-top bar. Beneath this device was a hidden trap door that led to a small room below, probably intended as a storage area for the bar. Sandy converted the space into a secret lair, setting up his broadcasting equipment there. A powerful antenna was needed to boost the signal of their messages to Rommel. After several unsuccessful attempts at installing one, the intelligence officer next door offered to help them. According to journalist Leonard Mosely, after positioning the antenna, their British neighbor exclaimed: “You could ruddy well broadcast to Hitler himself with that if you wanted to!" Eppler, grinning covertly to Hekmet jokingly replied: "And now excuse me, while I go in and call up Berlin!"

With the broadcasting equipment installed, it was time to signal Rommel’s listening station, to let the Nazis know that they had arrived in Cairo without incident. Eppler and Sandy encrypted their messages using a book code. The technique was simple. When the spies were given their assignment, they also received a copy of a specific book. To send their initial message, Sandy and Eppler turned to a page in that book that had been agreed upon in advance. They would then send a series of numbers corresponding to a specific letter on the page in question, identified by paragraph and letter number. With each passing day, the spies were to turn to the next page of the book and use that as the new basis for their coded communications. This ensured that each message was unique. In the absence of recognizable patterns, the only way to crack a book code is to know which edition of which book is being used—and which page is the basis for the code on any given day. One of the stranger aspects of Operation Condor was the volume that the Nazis chose for this purpose: an English-language edition of the classic 1938 suspense novel Rebecca, by Daphne du Maurier.

With Sandy ready to transmit sensitive secrets to Rommel, it was now on Eppler to root out some secrets that were worth transmitting. This would prove far more difficult than he, or his handlers, had imagined.

Eppler, Underground

A clubbable sort, Eppler’s first instinct was to gather intelligence by befriending British officers. When not hosting parties, he spent his evenings in all the places those officers frequented: the Continental Hotel, the Kit Kat Club, and Groppi’s tea rooms, a posh establishment owned by a Swiss expat. Eppler undertook these nocturnal activities as “Hussein Gaffer.” He tried a different approach during the day, sometimes assuming the identity of a British soldier. Donning a uniform from the Rifle Brigade, he went straight to the Turf Club. Founded in 1899, the Turf Club boasted a dining room and bar. Membership was reserved for notable British visitors and colonial officials, making it a reviled symbol of imperialism among many native Egyptians. Eppler took advantage of the lax admission policy that had emerged over the course of the current war, for a short time making the club his preferred destination for tasteful day-drinking.

Eppler passed the time standing at the bar and eavesdropping. Ever the extrovert, he would stand his new British friends one round of drinks after another, while never allowing them to pay for his. Though he tried his best to fit in, he eventually aroused the suspicions of one of the club’s patrons, who wondered what kind of Rifle Brigade soldier would turn down a free drink. Out of the corner of his eye, Eppler saw the man regard him with circumspection, then head in the direction of the payphone. Sensing that his cover was blown, he settled his tab and scurried out of the establishment, never to return. He had learned nothing of note.

Having struck out at the Turf Club, Eppler continued to party all night, while adopting a different spy tactic during the day. To that end, he attempted to expand his network of Nazi sympathizers living in Cairo. Numbering among these figures was young military officer—and future Egyptian president—Anwar Sadat. Eppler asked Sadat if he knew of any secret anti-British resistance groups active in Egypt. As it happened, Sadat was the right person to ask, being a member of the “Young Egypt Party,” a fascist organization also known as “The Green Shirts.” Like many his fellow party members, Sadat’s support of Hitler grew out of a fervent sense of nationalism, one that rejected Britain’s ongoing legal, economic, and cultural influence on Egypt. He hoped that an Axis victory would rid the country of the British for good.

In the end, though, Eppler and Sadat didn’t really vibe. According to more than one source, the Egyptian military officer tried to use Eppler to enter into strategic negotiations with Rommel. With the Allies being pushed back in the western desert, Sadat wanted to use the Egyptian military to attack them from behind as Axis powers assailed them from the front. As Mosley reports:

“He was convinced that the days of the British in Egypt were numbered. Students were already demonstrating in the streets, shouting and throwing stones at passing British lorries…"Now is the time to strike,” Sadat told Eppler. "We can turn the Delta into a blood bath if we rise now. Please tell that to your superiors and urge them to be ready to back us."

This all sounded a little too intense for Eppler, who was simply trying to answer the three questions that his spymasters had assgined him. Uttering something noncommittal, Eppler extricated himself from this conversation, obviously disappointing Sadat in the process.

In the Western Desert, the proverbial clock was ticking, and Eppler’s first couple of weeks in Cairo had failed to reap any useful intelligence. Meanwhile, the first cracks in Operation Condor’s well-laid plans were starting to show.

Bad Omens

Eppler and Sandy partied hard. Neither was the type to economize. They racked up such gargantuan tabs at the Kit Kat Club that they stood out conspicuously—this, in a cabaret notorious for its big-spending clientele. They ate nightly in the best restaurants, purchased cases upon cases of the finest liquor, and even found a way to spend absurd amounts of money on casual sex. At a low point in his productivity as a spy, Eppler met an alluring dancer named Edith, an exceptionally beautiful Egyptian of Jewish descent. On any given night, you could find Edith wandering around Cairo’s hotspots with a female friend. Before long, the two women were waking up several mornings a week in the houseboat of Sandy and Eppler. In addition to paying for lavish evenings out, the two spies paid Edith and her friend a king’s ransom each time they slept over.

Though the spies had arrived in Cairo with 50,000 British pounds, they began to worry about the dent that their current lifestyle was putting into their cash reserves. However, they soon had an even graver money problem. Unbeknownst to Eppler, most of the banknotes that his Nazi handlers had given him were counterfeit. This posed two problems. First, the counterfeits were so good that it was obvious that they had been printed by a government and not some smalltime crook. Once the British figured out that the fake money was German in origin, they also inferred that there were Nazi spies currently active in Cairo. Counter-intelligence workers began to map all the places where the dubious banknotes had been circulated, in an effort to identify the big-spending spies. Second, when Eppler’s money changer, an Egyptian Jew named Sami, attempted to sell some of the notes he had taken from the two spies, his associates recognized them as fakes. Sami, who had known Eppler for several years, helped the undercover agent exchange his dubious bills on the black market. As stands to reason, the exchange rate in the criminal underworld proved less favorable than the one offered by above-the-board money changers. This meant that everything would now cost Eppler and Sandy 2-3 times what it had before, accelerating the already-rapid depletion of their funds.

As bad as all this was, there were far worse problems on the horizon. In early June, soldiers from New Zealand—or possibly Australia—captured a group of Rommel’s radio operators in the Western Desert. They sent the prisoners to a newly-opened British interrogation center, located in the leafy Cairo suburb of Maadi. The building also housed the office of Major Alfred William Sansom, a British counter-espionage expert who was currently busy mapping the dodgy banknotes that were circulating in and around the city. Like Eppler, Sansom was a European who had been born and reared in Egypt. In addition to his native English, he spoke multiple languages fluently, including French, Arabic, and Greek. He had an intelligent face, with dark, slicked-back hair, and a nearly trimmed mustache.

Sansom was working on other things when a colleague named Bob came to talk to him. It was about the Nazi radio technicians. Under questioning, most had cooperated and were already being transferred to POW camps. However, two refused to talk under any circumstances. Sansom knew what this meant. The silent pair had no doubt been assigned to a special mission, one so sensitive that they were willing to take the secret to their graves. Bob had just gone through their belongings a second time and had turned up something that had previously escaped his notice. The two taciturn Nazis did not have any books in their lodgings, with one exception: an English-language edition of the bestselling novel Rebecca, by Daphne du Maurier.

In the first place, it didn’t seem as though the prisoners knew much English at all. Secondly, they didn’t really appear like the bookish sort. Bob also noticed that the price, originally written on the inside of the book, had been painstakingly erased. This struck him curious, so he sent the volume over to a forensic photographer, who recovered a faint trace of the original price: 50 escudos. The book had been purchased in Portugal. Bob put in an inquiry with military intelligence, who sent him the following telegram: “GERMAN MILITARY ATTACHE LISBON BOUGHT FIVE COPIES DU MAURIER’S NOVEL REBECCA IN MARCH 1942.” Sansom’s eyes lit up. In this moment, he had a hunch. These silent captives were almost certainly linked to the Nazi spies spending bad money all over Cairo. And their copy of Rebecca held the key to decoding any encrypted messages that they might be transmitting to Rommel. With the situation heating up in the Western Desert, Sansom would have to redouble his efforts to hunt them down. This would mean spending even more time undercover, chatting up the clientele of Cairo’s swankiest bars, music halls, and cabarets.

A Breakthrough

Eppler continued to hustle in vain for something juicy to send Rommel’s way. Meanwhile, Hekmet Fahmy seduced a string of British officers, occasionally extracting useful tidbits of information about the desert campaign. Then, one evening in early July, she had a breakthrough. As Hekmet sat backstage at the Kit Kat Club, there was a knock on her dressing room door. “Who’s there?” she asked. A servant answered that there was a British Major here to see her. Hekmet knew who it was. For weeks, she had been cultivating a relationship with an English officer who was privy to top secret information about the Western Desert campaign. Though she hadn’t let him get past first base, he had recently vowed to divorce his wife in order to marry the belly dancer. The sources that mention this unfaithful husband have kept his identity anonymous, referring to him as “Major Smith.”

In any event, Hekmet sensed that something important was afoot; she gave Major Smith permission to enter her dressing room. He arrived garbed in his desert uniform, carrying a dispatch case. Hekmet offered him a seat. As he sat, he pulled out a rectangular velvet box from his jacket and handed it to her. When she opened it, a gasp escaped her lips; it was an extremely expensive diamond and emerald bracelet.

Sensing her astonishment, Major Smith explained: “"I've been ordered to General Ritchie's headquarters in the desert…I have to deliver this [case] and then wait for further

orders. I don't know when I'll be able to get back, or even if I'll get back at all. So, I thought I would say good-bye—and leave you with a little keepsake."

Though distracted by her extravagant new bauble, Hekmet did not fail to realize that Smith was carrying something far more valuable in his bag. She thanked him gushingly for the emeralds, then redirected the conversation.

“How can I thank you? Is it so urgent? Must you go tonight?” she asked.

“[Yes],” Major Smith replied, “I shouldn’t even have taken time off to come here. They are waiting for these dispatches. We can't trust them to the radio or to an ordinary dispatch rider."

This was it! Hekmet had been waiting weeks for a chance like this one. Here, right in front of her, was a gullible, love-besotted fool carrying intelligence so sensitive that only a high-ranking officer was authorized to deliver it. She HAD to see the documents inside that dispatch case.

Hekmet turned on the bedroom eyes and coyly ran her fingers through her hair. Surely, the major had enough time to return to her houseboat so she could thank him… properly. It was just a matter of cancelling her last number of the evening and going home a little early. What difference would a couple of hours make? The major, excited by this apparent thaw in their relations, agreed.

When the pair arrived to Hekmet’s floating pad, she poured a round of drinks. She laughed at his jokes and stared at him longingly. There were probably even a few kisses exchanged. After some additional rounds, the belly dancer made her move. Concealing her hands, she dropped an opiate into Major Smith’s glass and served it up to him with a smile. A couple of hours—and a roll in the hay—later, Hekmet boarded the houseboat of Eppler and Sandy. “Come quickly,” she told them. The Allies’ plans for the Western Desert were in her bedroom, and the man carrying them might wake up any moment.

Comments