The Trial (S5E4)

- Gavin Whitehead

- Aug 4, 2025

- 30 min read

Updated: Aug 8, 2025

In 1937, former Mount Hermon employee S. Allan Norton was ambushed at home by a trespasser with a shotgun. Norton identified his attacker as Thomas Elder, prime suspect in the unsolved murder of Elliott Speer. Members of the community held their breath as Elder went to trial for the attempted murder of Norton, hoping that proceedings would shed light on the shooting of Headmaster Speer.

Above: In July 1937, Thomas Elder went on trial in the Franklin County Courthouse in Greenfield, Massachusetts. This was the same building that had housed the inquest into the death of Elliott Speer in December 1934. Image courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

SHOW NOTES

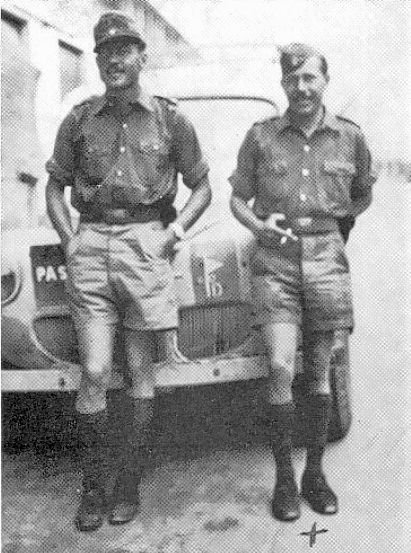

S. Allan Norton accused Thomas Elder of coming to his home late at night and pointing a shotgun at him. A longtime professional foe of Elder, Norton had retired as Mount Hermon’s cashier. This is a scan of an original press photograph, taken during the 1937 trial, that we purchased, with the help of listener donations.

This image of Thomas Elder in 1937 is another original press photograph taken that we procured and scanned for this miniseries. Taken as the trial was ongoing, the picture is highly staged, depicting Elder as calm, serene, and unconcerned by the accusations levelled against him.

Much of the trial ended up hinging upon an incident that had nothing to do with the gun-related charges brought against Elder. In 1930 (or ’31), Norton drilled a peephole in the wall that separated his office from Elder’s in order to ferret out adulterous activities between the dean and his secretary, Evelyn Dill. At trial, Dill and other witnesses contradicted Norton’s claim that he had seen her kissing Elder.

Postcard showing the Eagle Hotel in downtown Keene, New Hampshire, as it appeared in the 1930s. According to Thomas Elder and his wife, Grace, the former dean could not have assaulted Norton with a gun because the married couple spent all night at the Eagle. While the hotel’s front desk clerk avowed that Elder never left the building that evening, the chambermaid swore that only one person had slept in the Elders' bed.

R. C. Woodthorpe’s The Public School Murder benefitted from its association with the Speer case. The novel was reprinted by Penguin in 1940. The BBC adapted the book to radio under the title “Storm Over Polchester” (1963). In 1969, the BBC made a television version, which you can see announced in these broadcast notices. Despite these adaptations, the book and its author eventually fell into obscurity.

This is the last known photograph of Elliott Speer, taken at Mount Hermon’s 1934 graduation ceremony. While Elder’s name was forever tainted, Speer has been honored by generations of students. Today, a lounge on campus bears his name and a granite monument extols his virtues as an education and headmaster.

LINKS

"Storm over Polchester," a radio dramatization of The Public School Murder: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SM4D2irrnSQ&t=595s

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Manuscript Materials & Archival Documents

--Moody, Frances Wells. Northfield Recollections. Northfield, MA: Dickinson Memorial Library (loc 929.2 Moody).

--Speer, Robert Elliott. Robert Elliott Speer Manuscript Collection. Princeton, NJ : Princeton Theological Seminary:

*Clippings and Mimeographed Material : Northfield schools. 1917-1942. - Northfield and Mt. Hermon Reports (Series VII: Clippings and Mimeographed Material. Subject File; Box 130, File 130:6).

*Letters Concerning Elliott Speer, 1915-34 (Series II: Correspondence; Box 25, File 25:5).

*Letters Concerning Elliott Speer, 1934 (Series II: Correspondence; Box 26, File Box 27, File 27:1-8).

*Letters Concerning Speer, Elliott. 1898 (Series II: Correspondence; Box 25, File 25:6).

*Letters: Family letters, 1911-1936. Folder 2 (Series II: Correspondence; Box 20, File 20:7).

--Various census records, passport applications, war records, yearbooks, birth and marriage certificates, Mount Hermon ephemera.

Books & Dissertations

--Amende, Coral. The Crossword Obsession: The History and Lore of the World’s Most Popular Pastime. New York: Berkley Books, 2001.

--Carter, Burnham. So Much to Learn. Gill, MA: Northfield Mount Hermon School, 1976.

--Coyle, Thomas. The Story of Mount Hermon. Mount Hermon, MA: The Mount Hermon Alumni Association, 1906.

--Curry, Joseph Robert. Mount Hermon from 1881 to 1971 : An Historical Analysis of a Distinctive American Boarding School. Ph.D. dissertation: University of Massachusetts Amherst, 1972.

--Day, Richard Ward. A New England Schoolmaster: The Life of Henry Franklin Carter. Bristol, CT: The Hildreth Press, 1950.

--Edwards, Martin. The Golden Age of Murder. London: HarperCollins, 2015.

--Edwards, Martin. The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books. Scottsdale, AZ: Poisoned Pen Press, 2017.

--Marsden, George. Fundamentalism and American Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

--Piper, John F. Robert E. Speer: Prophet of the American Church. Louisville, KY: Geneva Press, 2000.

--Straton, John Roach. The Menace of Immorality in Church and State. New York: George H. Doran, 1920.

--Symons, Julian. Bloody Murder: From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel, a History. London: Faber & Faber, 1972.

--Symons, Julian. The Detective Story in Britain. London: Longman, Green & co., 1962.

--Walley, Craig. Murder at Mount Hermon: The Unsolved Killing of Headmaster Elliott Speer. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004.

--Woodthorpe, R. C. Una bala para el señor Thorold. Tr. María D. A. de Derisbourg. Buenos Aires: Clarín/Emecé, 2015.

Periodical Articles

--Carter, Burnham. “The Study of a Murder,” in Yankee: October 1977, p. 102

--“Dogs Reveal Speer Killer As Household Intimate,” in Daily News (New York, NY): Sep. 19, 1934, p. 11

--“Headmaster Murdered Just as in Novel,” in Daily Express (London, UK): Dec. 4, 1934, p. 1

--Lyman, Loren D. “Mystery Deepens in Speer Slaying” in New York Times : Sept. 20, 1934, p. 48.

--Manchester, Harland. “The Headmaster Murder Mystery” in American Mercury: August 1934, p. 410

--“Mount Hermon Opens,” in The Northfield Herald : September 28, 1934, p. 1

--“Ousted Student Sought in Death of Elliott Speer,” in New York Herald Tribune : Sept. 16, 1934, p.15.

--Pearson, Edmund. “Say, Who D’ye Think Done This, Anyhow?” in New York Herald Tribune: July 21, 1935, p. F3

--“Says Speer Suspect Set Clocks Ahead,” in New York Times : Dec. 8, 1934, p. 7.

--“Speer’s Killer ‘To Be Seized Next Monday’” in Daily News (New York, NY): Dec. 1, 1934, p.6

--Taylor, John Jr., “Elder Jailed Despite Denial,” in Daily Boston Globe: May 27, 1937, p.1

--Taylor, John Jr., “Letters to Fore in Speer Case,” in Daily Boston Globe: Dec. 5, 1934, p. 1

--Taylor, John Jr., “Thrash Norton, Elder Threat: Dr. Cutler Says Dean Angry at Peek Story” in Daily Boston Globe : July 27, 1937, p. 1

--"Thomas Elder Takes the Stand,” in Waterbury Evening Democrat: July 27, 1937, p.1

--Thompson, Craig. “Eder Is Acquitted on Assault Charge,” in New York Times : July 29, 1937, p.1

--Approximately 400 additional pieces, from publications such as: The Boston Globe, The Brattleboro Daily Reformer, The Burlington Free Press and Times (Burlington, VT), Daily Express (London, UK), Daily News (New York, NY), The Daily Recorder-Gazette (Greenfield, MA), The Inverness Courier, New York Times, The Northfield Herald (Northfield, MA), The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Springfield Daily Republican, The Springfield Sunday Union and Republican, The Washington Times…and a few dozen others.

TRANSCRIPT

The sleepy town of Greenfield, Massachusetts isn’t the kind of place where people minding their own business get gunned down in their garages. Even so, that very thing almost happened on the evening of May 25, 1937. As the hour approached 11:00PM, a full moon bathed the town’s streets in a soft, pearlescent light. Most Greenfield residents were nestled in bed.

Seventy-one-year-old S. Allen Norton was among those who were still awake. Recently retired from the Treasurer’s Office at Mount Hermon School for Boys, he was driving home with his wife. A tall, heavyset man with a cloud of silver hair, Norton lived at 71 Haywood Street, in a tidy neighborhood of modest two-floor houses, sitting relatively close to one another. The couple was returning from a late-night church gathering, pulling up to the front of their home around 11. Norton dropped his wife at the front door of the house and drove around to the back to their garage. He stopped and stepped out of the car, raising the garage door. He got back into the driver’s seat and pulled into the building. As he exited the car a second time, a disembodied voice commanded, “Get back in that car. I want to talk to you.” Norton reflexively flinched.

Outside the garage, the figure of a man arose from the shadows. He was shorter than Norton and wore a hat along with a long, dark overcoat that hung down to his ankles. Norton, frozen in place outside his car, stared as the silhouetted man produced a shotgun that he had concealed in his coat. The stranger advanced, his firearm leveled at Norton, until he entered a beam of moonlight. In this moment, a terrified Norton realized that he knew this gun-wielding prowler; it was Thomas Elder, former dean of Mount Hermon and the man believed by many to have murdered Elliott Speer three years earlier, in 1934.

In the years since the killing of Elliott Speer, Thomas Elder’s life had taken more than one hard-left turn. But the biggest surprise of all was when he landed back in the headlines, in connection with yet another gun-related crime. Today, we’ll hear about Elder’s activities after the inquest into the Mount Hermon shooting, how his bitter rivalry with a co-worker launched him into criminal court, and how this trial brought fresh attention to the unsolved murder of Elliott Speer. This is The Art of Crime, and I’m your host, Gavin Whitehead. Welcome to part four of Murder by the Book . . .

The Trial

After the Inquest

For Dean Thomas Elder, it didn’t matter much that the inquest into the death of Elliott Speer failed to identify him as the perpetrator or even a suspect. Many faculty members and trustees continued to believe that he shot and killed the former headmaster. This atmosphere of anger and suspicion made it impossible for the dean to return from the leave of absence he had taken following his all-night interrogation by state police. In early 1935, Elder resigned his position at the school where he had first arrived as a student in 1907 and spent most the following 27 years in various official capacities. He moved out of state with his wife and adult son, Thomas Jr., relocating to the small town of Alton, New Hampshire, where the former dean tried his hand at poultry farming. This line of work did not make him wealthy by any means, but he was able to supplement his income as an expert consultant in the breeding of Holstein Cows. Thanks to this sideline, the Elders frequently traveled to dairy conventions throughout New England, and Elder himself made many admiring friends throughout the industry. When at home on his farm, he frequently attended services at the local Congregationalist church and quickly became President of the Alton’s Men’s Forum.

As the Elder family was building this new life, investigators kept a close watch on their prime suspect in the murder of Elliott Speer. Even though Thomas Elder lived in New Hampshire, the Massachusetts police maintained a log of his incoming mail from 1934 through at least 1937 and may have even read some of it. During the same years, plainclothes detectives often shadowed his movements, including his attendance at meetings of the Holstein-Friesian Association of America, a professional body dedicated to these two cattle breeds.

For reasons that would not become known to the public until after Elder showed up at Norton’s house with a shotgun, the authorities were also monitoring the mail and phone calls of Miss Evelyn Dill, Elder’s former secretary at Mount Hermon. Thin, red-haired, and far younger than Elder, Dill had a conspicuously close relationship with her boss. Elder had taught her to drive, and the two of them were rumored to have gone on road trips together to Boston and Brattleboro,Vermont. The scrutiny to which Miss Dill was subjected strongly suggests that the police suspected either that she was an accomplice to the murder of Elliott Speer, or that Elder might eventually confide his secrets to her.

While all of this was happening behind the scenes, the Speer case itself had evaporated from headlines. For a while, it seemed as though the murderer would never be apprehended—and that the mystery would eventually melt away into obscurity. But then, a breathtakingly bizarre event reignited public interest in the crime.

Allegations

Which brings us back to the evening of May 25, 1937. According to him, Norton stood, motionless, as Elder approached ever closer to the garage door, shotgun leveled at him. Elder called out in a masterful tone: “Do as I say and get back in that car. I’m going to talk to you.” Obeying was not an option for Norton—he could flee, or he could die. Twisting away from the gunman, Norton scrambled around to the back of the car, keeping low to the ground. Elder tied to follow him with the muzzle of his gun, but Norton was too fast. The retired school cashier hurled himself through the door that connected the garage to the kitchen. He tumbled in, first slamming, then locking, door. He yelled to his wife, in a panicked, rattling voice, “Tom Elder is outside with a gun ready to shoot me. Call the police.” Mrs. Norton, who was already approaching the kitchen from the coat closet, stared in mute bewilderment. For a few seconds, the married couple simply looked at each other. Snapping out of her stupor, Mrs. Norton turned off the lights in the kitchen and living room, so that Elder could not see their movements from the outside. Then, staying close to the ground, she picked up the telephone and called the police.

By the time the Greenfield P.D. arrived, there was no sign of Elder. Upon entering the house, Mrs. Norton directed the officers upstairs, where her husband was hiding. Even though the police assured him that all was clear, Norton refused to accompany them outside. It took several minutes to coax the terrified man downstairs and out into the driveway. Norton walked the authorities through the confrontation. They, in turn, notified the Massachusetts state police. Within hours, there was a warrant out for Elder’s arrest. State detectives sent out a teletype advising police stations across Massachusetts that Elder was wanted for questioning.

The following afternoon, New Hampshire state police apprehended Elder at his farm in Alton. Their job was to hold him in custody while Massachusetts authorities applied for his extradition across state lines. During his initial arrest, Elder was chatty and high-spirited, gabbing away with New Hampshire policemen. He wasted no time in contacting his lawyer, Charles R. Fairhurst, a former D.A. who had represented him during the Elliott Speer inquest. Fairhurst advised his client not to contest the extradition and promised to get him a speedy hearing. Back in Massachusetts, Elder was charged with assault with the attempt to murder, a serious felony. The judge set his bail at $10,000, a sum that the prisoner could not hope to pay. Nevertheless, with the help of family and his friends in the cattle-breeding industry, he was out of jail by May 28. Elder would not see the inside of a courtroom again until June 3, when a hearing would decide whether or not his case would be forwarded to a grand jury. In the meantime, he was out on bail.

Given the nature of the crime and the identity of the accused, the story of Elder’s arrest drew fervid, nation-wide newspaper coverage. The unspoken idea that Elder had artfully dodged homicide charges during the Speer inquest underpinned many of the stories about this more recent gun-related offense. Headlines speculated that information learned in the course of the current investigation would at last solve the mystery of the Speer shooting. The Washington Times printed a photo of Elliott and Holly Speer, accompanied by the caption: “OLD MYSTERY REVIVED : New Murder Clue.” United Press International, a syndicated news service, went with the somewhat less snappy though equally suggestive “Elliott Speer Murder May Be Joined With New Crime.” At first glance, none of this seemed like a particularly great development from Elder’s perspective. Back in 1934, the press had only hinted at his status as prime suspect in the Mount Hermon shooting and never identified him by name. Now, the whole world knew that he was the person thought to be responsible for the murder of the idealistic young educator. Apart from outing Elder as the suspect, these news stories could potentially taint the jury pool, who just might come into court believing that the defendant was capable of menacing a former colleague with a shotgun because he had already shot and killed another colleague in the past. Both attacks, moreover, had taken place at the victim’s private residence.

Perhaps surprisingly, neither Elder nor Fairhurst shied away from the press onslaught. During the Speer inquest, Elder sidestepped reporters and photographers; this time, he and his attorney mounted a cleverly orchestrated media campaign. To the press, Elder and Fairhurst projected total confidence that the simple poultry farmer would be exonerated of all wrongdoing. Headlines trumpeted the lawyer’s demand that his client be allowed to take a polygraph test; the former dean took things a step further by challenging Norton to do the same. Meanwhile, a smiling Elder gladhanded journalists as though he were running for political office, not defending his life. Even before Elder’s arraignment, the general contours of his legal defense snapped into view on front pages throughout the U.S. At this early stage of things, it was clear that this defense hinged on savaging the character of the putative victim, S. Allen Norton.

Elder’s Story

Thomas Elder categorically denied traveling to Norton’s home the evening of the crime. He claimed that, on the night in question, he and his wife, Grace, were staying at the Eagle Hotel, in downtown Keene, New Hampshire—some thirty-three miles (roughly fifty-three kilometers) away from Greenfield, Massachusetts. Both Mr. and Mrs. Elder swore that they had spent the previous day in nearby Brattleboro, Vermont, where they were visiting the secretary of the Holstein-Friesian Cattle Association. In previous weeks, Thomas Elder had been experiencing cardiac difficulties. He was still recovering and felt too tired to make the entire 100-mile return journey from Brattleboro to Alton. So, the Elders decided to spend the night in Keene, a town that they had visited in the past. They checked into the Eagle at 7:00PM. According to the couple, they both retired to their room around 9:00PM, and neither left the room until they checked out the following morning, at 7:00AM. Then, they returned to their farm in Alton, ignorant of the trouble that had gone down in Greenville. Elder added that the accusations against him were either the result of mistaken identity or deliberate deception on the part of Norton.

For his part, Norton was not as hands-on with the press, staying more or less mum in the early stages of the legal process. When asked about Elder’s professions of innocence, Norton did respond that he had known the former Mount Hermon dean for almost three decades and could not possibly have mistaken him for someone else, especially by the light of a full moon. While Elder tended to be punchy and memorable in his answers, Norton replied to questions in vague, at times enigmatic terms. When a reporter asked him if he knew of any reason why his former co-worker might want to kill him, he replied: “Yes, I do, but I won’t tell you.”

The world would have to wait until the court hearing of June 3 to hear the story of the ancient beef between the two silver-haired retirees. The narrative that unspooled in the courtroom proved more salacious than anyone would expected, and it began to make sense why Norton would have preferred to keep it to himself. We’ll hear more after a quick break.

The Hearing

Local and national media outlets made Elder’s June 3 hearing front-page news. On one side was Assistant District Attorney Henry Herr, who would attempt to convince Judge Philip H. Ball to greenlight a grand jury trial. On the other side was Elder’s seasoned attorney, Charles Fairhurst. The unsolved homicide of Elliott Speer hung over the County Courthouse throughout the hearing. The public, hopeful that Thomas Elder’s legal woes would shed light on that older mystery, packed every seat in the courtroom, and spilled out into the street. Things got so crowded that reporters were moved to the prisoner’s dock, which—because this was a hearing and not a trial with a defendant—was empty.

The hearing was relatively short. S. Allen Norton was, by far, the most important witness. In exact speech that one reporter called “academic,” Norton answered the D.A.’s questions about Elder’s alleged attempted assault on him. The most dramatic juncture of his testimony came when he pointed at Elder to identify him as the person who had aimed a shotgun at him.

This was straightforward, even dry. But things turned unexpectedly juicy during cross-examination. Fairhurst’s questioning of Norton focused on an incident from the distant past, one that ostensibly had zero bearing on whether Tom Elder had waved a shotgun at him. In part three of this miniseries, we talked about the ploy that District Attorney Thomas Bartlett enacted against Elder during his investigation into the murder of Elliott Speer. At the end of a long workday at Mount Hermon, the D.A. asked the dean if he had a few minutes to speak with him. Elder answered in the affirmative, and moments later, a squadron of seven armed detectives descended on his office and subjected him to a heated interrogation lasting until four or five in the morning. As I mentioned in passing, Elder answered every single questions with one curious exception: Did he know anything about a peep hole at Mount Hermon? When confronted with this topic, the dean clammed up, refusing to comment without an attorney present. Three years later, Fairhurst’s cross-examination would not only explain this inscrutable exchange, but also cast the Mount Hermon School for Boys in a sleazy light.

The incident in question happened in 1930 or 1931, before Elliott Speer had become headmaster of the school. Rumors were aswirl about a torrid romance between Dean Elder and his pretty, young secretary, Miss Evelyn Dill. This gossip came to the attention of Cashier S. Allen Norton, who just so happened to have an office adjacent to Elder and Dill’s.

Norton had an axe or three to grind with Elder. Much to S. Allen ’s annoyance, the dean often meddled in the operations of the Treasurer’s Office, where Norton served at different times as treasurer and cashier. But their hostilities predated this turf war. When Elder was attempting to volunteer with the YMCA during World War I, Norton maligned him to prominent officials in that organization, alleging that he should not be trusted with any position of authority or responsibility. Then, in 1926, Headmaster Henry Cutler—Elliott’s predecessor at Mount Hermon—appointed Elder dean of the school, a brand-new position. In creating the office of dean, Cutler effectively eliminated the position of vice principal, which was held by Norton’s brother, who—thanks to Elder’s promotion—lost his job. From this time forward, Elder and Norton made little to no effort to conceal their mutual feelings of animosity. Most recently, in 1934, Norton provided testimony that cast Elder in a dubious light during the inquest into the death of Elliott Speer.

So, Norton’s ears perked up when he heard whispers of untoward intimacy between Miss Dill and his married nemesis, Dean Elder. A tireless defender of morality and family values, Norton resolved that the Christian thing to do would be…to drill a secret peep hole in the wall that separated his office from Evelyn Dill’s. The aperture allowed him to engage in some morally upright, not-at-all pervy surveillance of his co-workers. Sadly, we will never know how many long and trying hours Norton spent ogling the young secretary in his vigorous defense of traditional marriage. However long the stakeout took, he eventually claimed that he had spied Elder crossing a professional boundary with Dill on top of her desk. Norton continued to keep a long, hard watch on the tryst—just to see exactly how much sin was being committed.

Armed with tales of desk-top ecstasies, Norton tattled to Dr. Henry Cutler. The headmaster was taken aback. To the best of his knowledge, Elder was a strict fundamentalist Christian, a family man very much devoted to his wife. Circumspect about Norton’s claims, Cutler enlisted the school’s superintendent of buildings, Richard Watson, nicknamed “King,” to help investigate. Watson was as much an institution as Mount Hermon School for Boys. In fact, he was part of the first class of boys ever admitted to the institution when it opened its door at the end of the nineteenth century. Watson spent his entire career at Mount Hermon. Known for his fiery temper, King always sported a bright red tie that reflected this facet of his personality. Each year, the students pooled their money to buy him a replacement. Under the administration of Elliott Speer, Elder and Watson, who had long been friendly, became close allies as members of the conservative faction of the faculty and staff. He would stand by Elder throughout all his recurring legal troubles. Along with the conservative Dr. Henry Cutler, Watson remained one of few Mount Hermon personnel who never shunned the former dean.

Back in 1930, Cutler and “King” Watson staged a forensic re-enactment of Elder’s tryst with Dill while investigating Norton’s allegations. To that end, the headmaster sat on Evelyn Dill’s desk while the superintendent of buildings peered through the hole in the wall. The idea behind this exercise was probably to test whether or not Norton could have seen what he had claimed to from that vantage point. It’s unclear what else the headmaster did to investigate the allegations of sexual impropriety, but—in the end—nobody lost their job.

Cutler succeeded in keeping knowledge of the allegedly adulterous escapade from the public. His primary interest was in squelching the mutual animosity between Elder and Norton. In order to put an end to the whole tawdry affair, Cutler summoned Mr. and Mrs. Elder and Mr. and Mrs. Norton for a prayer meeting, which culminated in all four bending at the knee and praying for guidance and forgiveness. As will become evident, those involved in this picturesque office ritual disagreed about its particulars—and these disagreements proved central to the criminal charges against Elder in 1937.

Fairhurst seized on this sordid chapter in Mount Hermon’s history and ran with it. He asked Norton about his voyeurism and the events surrounding the prayer meeting. The courtroom exchange that followed is so excruciatingly juicy that I didn’t dare summarize it. Here is the actual dialogue, in the two men’s own words—

Norton: Yes, that [prayer meeting] was about some information which came to me.

Fairhurst: You got that information through a peephole, did you not?

Norton: Yes, if you want to call it that.

Fairhurst: As a matter of fact, didn’t you bore a hole from the closet of your office in

the School Administration Building into Elder’s room?

Norton: No. Into Miss Dill’s.

Fairhurst: Then you spied on him deliberately?

Norton: Yes. It was my duty to the school.

Fairhurst: And you peeked?

Norton: Yes.

Fairhurst: And you peeked often, didn’t you? All the time, in fact?

Norton: No, I should say that three times was the limit.

Fairhurst: And didn’t you have to kneel down to peek? Get down on your hands and

knees?

Norton: No, nothing like that.

Fairhurst: But didn’t you have to stoop way over to see through your peekhole?

[At this point in the questioning, Fairhurst himself stooped low, to the point that his knees almost touched the courtroom floor.]

Norton: No, the hole was the same height as a desk from a floor.

[ Here, I had to wonder: Just how tall does this guy think the average desk is? Surprisingly, Fairhurst let this last nonsensical answer slide.]

Fairhurst: Anyway, you saw something and went to Cutler and this meeting was held?

Norton: Yes.

Fairhurst: The next day did you see Mr. Cutler and apologize to him and Elder for what you said?

Norton: I did not apologize.

Fairhurst: Did you kneel down and pray?

Norton: Yes.

Fairhurst: Did you kneel down and ask God to forgive you for being such a miserable skunk as to spy on Elder and Miss Dill?

Norton: I cannot tell you what I said in prayer. It was not that, though. I will tell you the story if you will give me a chance.

Fairhurst: Don’t do that. I don’t want you to pray here. You asked God to forgive you for what you said about Elder and Miss Dill, didn’t you?

Norton: No. We were all praying. We were on our knees.

Fairhurst: Did you have any other peepholes around the school?

Norton: [Hesitating] No.

In the end, Fairhurst cross examined the alleged victim for thirty punishing minutes. His line of questioning didn’t merely seek to discredit Norton; it was meant to humiliate him. In the stand, the witness came across as squeamish, pedantic, and evasive; the questions themselves painted him as a peeping Tom, a hypocrite, and an officious little narc. Throughout the fiasco, Elder could be seen smirking amid bouts of furious note-taking.

Fairhurst had done serious damage, but the testimony of two additional witnesses called by the state reinforced Norton’s account of the incident on May 25. The first was Yvonne Arsenault, a young French-Canadian maid who worked in the house neighboring Norton’s. Though she didn’t know much English, the French-speaking Arsenault labored her way through the story of what she had seen on the evening of May 25. Late at night, as she was looking out her upstairs window, she witnessed a man with a long dark coat and a gun in the Norton’s driveway. He bellowed “Hey!” as he approached the garage. Though she could not identify the man, his testimony suggested that Norton had told the truth, that someone had accosted him at home that night.

The second was Edith Weymouth—a neighbor living in yet another house. Weymouth heard shouting and then a car speeding down the street around 11:00PM. More important, she swore that she had observed a black sedan creeping up and down the street earlier in the evening—around 9:00—as though it were stalking someone. Though she didn’t catch the license plate number, she noted that the plates themselves were white with green lettering. (At the time, the only state that issued such plates was New Hampshire, where Elder resided.)

The prosecutor rested his case. For his part, Fairhurst called no witnesses. Instead, he appealed to the judge to dismiss the charges against his client. Fairhurst argued that the state had failed to call a single witness that corroborated Norton’s allegations. This was an especially grave fault in the case because Norton had shown himself to be an untrustworthy person, who had a grudge against Elder and was completely unashamed to spy on friends.

The judge was not swayed by these arguments. He found probable cause to send the case to a grand jury. This next proceeding, to be held the second week of July, would determine whether there was enough evidence to issue an indictment against Elder. If an indictment were returned, a trial would follow shortly thereafter.

Though his attorney failed to get the charges against him dismissed, Elder spun the hearing as a victory for him. He gloated that he was eager to get his case heard by a jury of normal citizens, who would no doubt see through the sham charges leveled against him. Elder had primed reporters to give him favorable coverage, smiling at them periodically throughout the hearing. Even in the most incriminating moments, he made sure he appeared calm and collected to members of the press. His assiduous notetaking caused one reporter from the Daily Boston Globe to characterize his behavior as “more like an associate counsel than a defendant.” He and his lawyer had lost on legal grounds, but they scored a minor win in the court of public opinion.

The Trial – Thomas Elder’s Motive, Means, and Opportunity . . .

As everyone expected, the grand jury returned an indictment against Elder in mid-July. The criminal trial was scheduled to begin on July 22 in Greenfield’s Superior Court. The press underscored the fact that this was same courthouse that had served as the setting for the inquest into the murder of Elliott Speer in December 1934. Due to the defendant’s link to the Speer case, a crash of journalists and roughly 100 members of the public stuffed themselves into the tiny courtroom. One newspaper estimated that 90% of the spectators were women. Over the course of the three-day trial, there was a palpable expectation that the identity of Elliott’s murderer would finally come to light. This belief was reinforced by the fact that the detectives who were now in charge of the Speer investigation sat in the back of the courtroom, taking careful notes on the proceedings.

The state’s theory of the case hadn’t changed much since the hearing. The prosecution maintained that Elder had absconded from his hotel in Keene, New Hampshire and driven to Norton’s home, arriving around 9:00PM. Seeing that Norton was not at home, Elder prowled the neighborhood, during which time Edith Weymouth witnessed him driving up and down the street. He kept an eye on the Watsons’ home until he saw them arrive from church service around 11. With Mrs. Watson inside, he confronted Mr. Watson on the threshold of the garage, pulling a gun. At this moment, the neighbor’s maid Yvonne Arsenault looked out the window and saw the defendant dressed in a long black coat, his weapon drawn. Then, Watson successfully gained entry to his house, causing Elder to flee in his car, the noise of which disturbed Edith Weymouth. Driving back to Keene, Elder sneaked back into the Eagle Hotel unseen. The following morning, he pretended as though he had never left, checked out of the hotel, and drove back to Alton.

There was, however, one significant development in the prosecution’s argument. It involved the question of motive. A lot of the news coverage of the case speculated that Elder’s motivation was related to the ongoing police inquiry into the Speer murder. A couple of reporters managed to confirm that Norton had recently spoken with the detectives who were investigating the mysterious shooting, which seemed to back up that thinking. However, in court, the prosecutor suggested a different reason for going after Norton. In recent years, Elder had been dunning the Mount Hermon School for Boys for a pension, insisting that he was, for all intents and purposes, broke. However, the former dean had a secret savings account with a few thousand dollars in it at the Franklin County Trust Company in Greenfield. Coincidentally, this was the same bank where Norton took a part-time job when he retired from Mount Hermon. According to prosecutors, Elder knew that Norton knew about this clandestine account—and attempted to silence him in the interest of securing his pension.

Part of the defense’s strategy was to establish an ironclad alibi for the accused. To that end, the defense called both Thomas Elder and his wife, Grace. Elder swore up and down that he had spent the entire night at the Eagle Hotel. Furthermore, he strenuously denied ever wearing the sort of long, dark overcoat that Norton had claimed to see him wearing on the night in question. Grace backed up her husband’s assertions. Then there was Harry Ferguson, the night clerk stationed at the Eagle Hotel’s front desk. An older, soft-spoken man, he related to the court that he often passed the time at work by reading romance novels, “one per night.” Even though he usually had his nose buried in a book, his position at the front desk afforded him a clear view of the only stairway that guests could use to exit the hotel. On the evening of the alleged attempted assault, Ferguson asserted, Thomas Elder did not come down those stairs. In light of this testimony, Elder appeared to have a rock-solid alibi.

But given the chance to present a rebuttal, the prosecution chipped away at this evidence. Russell Batchelder, who owned and worked at a gas station in Keene, had served Elder on the day of the alleged attempted assault on Norton. He distinctly remembered seeing Elder wearing a long dark overcoat. The state also produced a chamber maid employed by the Eagle Hotel, who testified that when she cleaned the Elder’s room on the morning that they checked out, it was clear that only one person had slept in the bed. Finally, the prosecutor introduced photographs of the hotel lobby, which showed that the view from the front desk to the staircase was partially obstructed, undermining the testimony of Harry Ferguson.

. . . S. Allen Norton’s Pervy Little Peephole

But let’s be honest: Reading through accounts of this trial leaves you with the impression that the question of what happened at Norton’s house on the evening of May 25th was of secondary importance. Thanks to a shrewd tactic on the part of the defense, the court proceeding at times seemed less like an inquiry into an attempted murder than a referendum on S. Allen Norton’s pervy little peep hole.

As he had done at the preliminary hearing, Fairhurst took sadistic pleasure in grilling Norton first about his longstanding rivalry with Elder and second about his vigilante voyeurism. This time, Norton’s answers about the workplace spying were far less weaselly:

Fairhurst: Did you report a scene between Elder and Miss Dill to Dr. Cutler.

Norton: Yes.

Fairhurst: Was it something got by spying on him?

Norton: Yes.

Fairhurst: What was it that you reported to Dr. Cutler?

Norton: I reported having seen him kiss his stenographer and having seen him and his

stenographer in each other’s embrace.

Asked whether he had ever retracted—or apologized for—his allegations of workplace smooching, Norton stated that he definitively had not. Over the course of several hous, the defense called multiple witnesses to dismantle Norton’s account of the peephole incident.

First came Richard “King” Watson, the cantankerous building superintendent who never came to work without his bright red tie. Under direct examination, the short, severe man with spikey gray hair blew a hole in Norton’s testimony. According to Watson, Norton had never accused Elder of kissing and embracing Miss Dill. Instead, the school cashier spoke about a very different display of affection, known as a “chin chuck”—a gentle touching or stroking of the area under chin. Starting with Watson’s testimony, there would be record-setting levels of talk about chin-chucking in this courtroom. According to Watson, it wasn’t until recently that Norton had punched up his account to include hugs and kisses. But that was all beside the point, Watson went on, because back in the early 1930s, Norton admitted to making up the whole story about the secret relationship between the dean and his secretary.

Next came Dr. Cutler, former headmaster of Mount Hermon. A learned, carefully spoken man in his mid-seventies, Cutler talked at length about the peephole controversy, supporting Watson’s claims about both the “chin-chuck” and Norton’s eventual recantation.

Of these three witnesses, one proved more hotly anticipated than the others: Miss Evelyn Dill. Prim and respectable, she behaved as if she would sooner drop dead on the stand than even so much as hint at the existence of sex, an affect doubtless encouraged by Fairhurst. She entered the courthouse early that morning draped in a drab overcoat. Underneath, she wore a modest dress, in a very business-like shade of navy blue. On the stand, she forcefully denied ever kissing or embracing Elder. She certainly hadn’t participated in an adulterous liaison with him. Even more striking, she claimed that Norton had apologized to her for making up all that stuff about “chin-chucking.” This was the third witness in a row to contradict Norton’s assertion that he had never gone back on his accusations.

Because the defense had made so much of Peepholegate, the prosecution had no choice but to address the scandal, further detracting from the question of whether Elder had attempted to harm Norton. In some cases, the district attorney was able to extract testimony that would not necessarily play in Elder’s favor under cross-examination. For example, seeking to prove that Elder held a violent grudge against Norton years after the peephole squabble, the prosecutor entered a personal letter from the former dean to Dr. Cutler into evidence. The document was written in 1935, amidst the ongoing police inquiries into the murder of Elliott Speer. In the letter, Elder blamed Norton for the negative attention he was currently receiving from authorities: “I think I am not wrong in believing that Mr. Norton had used the story about Miss Dill he started under your administration. That kind of gossip, contemptible as it is, may have found fertile ground in the gossip-loving brains of some of the investigators as well as in certain types of minds at Mount Hermon.” The D.A. also got Cutler to admit that Elder had expressed a desire to “thrash Norton.” Yet the prosecutor was markedly less successful in cross-examining Watson and Dill. When he tried to get Watson to walk back some of his claims about Norton and the peephole fiasco, for instance, the witness refused to back down, and his famous temper began to reveal itself. Scarcely able to conceal his contempt for the lawyer, Watson all but shook his fist from the box, only settling down when the judge intervened.

Just as the prosecution had been building a case against Elder, so the defense had been assassinating the character of the state’s integral witness, S. Allen Norton. Before the jury retired to deliberate on the third and final day, Fairhurst sent them off with a withering assessment of the school-cashier-turned banker. Remember, he advised the jurors, nobody but Norton had positively identified Elder as the assailant, nor had anyone seen him leave the Eagle Hotel on the night in question. And was S. Allen Norton’s testimony credible? Obviously not. The evidence had shown that Norton held a bitter grudge against Elder—not the other way around—and more to the point, Norton was the kind of guy to fabricate allegations against his adversaries. He had made as much plain with his vicious lies about workplace chin-chucking. His character was further called into question by the unsettling peephole gouged into his office wall. How could anyone possibly credit the word of such a meddling, mendacious debauchee?

After the prosecution and defense had made their closing remarks, Judge Hammond sent the jury away to deliberate. An hour passed, then two, then three. They were clearly wrangling over this one, and who can blame them given all the contradictory testimony they had heard? Perhaps anticipating a lengthy wait, the Nortons went home. Then, at 4:30PM, a little more than five hours after deliberations began, word came down that the jury had reached a decision. The jury’s foreman stood in court and solemnly announced the verdict: not guilty. A cacophony of murmurs and exclamations filled the courtroom as the judge ordered the release of the defendant. After nearly two months on the precipice of prison, Thomas Elder was free to go.

The trial left many disappointed, not just because Elder had gone free but also because no light had been shed on the murder of Elliott Speer. Apart from a handful of vague yet noteworthy allusions, his murder went unmentioned in open court. Yet this should come as no surprise, since addressing the clouds of suspicion that hung over Elder regarding the 1934 slaying would have prejudiced the jury against him. Indeed, in retrospect, it’s unclear why anyone ever expected this proceeding to yield answers about the violent end of the former headmaster.

Epilogue

Officially speaking, this trial had not generated any new insight into the unsolved murder of Elliott Speer. But to many, Norton’s allegations were convincing and provided additional evidence of Elder’s violent, furtive character. Even so, Thomas Elder resumed a normal life back on his New Hampshire farm and was severing as Selectman of the town of Alton as early as 1940. He continued to be an important figure in the Holstein world. Elder had no further brushes with the law. He died of a stroke in 1948, at the age of sixty-six, in New Jersey, while attending a conference on cattle breeding.

His passing made news throughout the country. In nearly every obituary, a couple of sentences were dedicated to his personal achievements. The rest of the text described the dubious role that he played in the murder of Elliott Speer and in the attempted murder of S. Allen Norton. As many people saw things, Elder’s death put a definitive end to any hope that the mystery of Elliott’s shooting would ever be solved.

Elliott’s wife, Holly, never remarried. In order to support her three daughters, she worked as headmistress at a series of prestigious girls’ schools before becoming the Director of the Experiment in International Living, a study abroad and cultural exchange program. Holly died on Monday, November 8, 1976—at the age of 80. She was survived by her daughters.

As for R.C. Woodthorpe and his novel: The Public School Murder benefitted from the notoriety brought to it by the Mount Hermon shooting. It was reprinted in a green paperback edition in 1940, as part of Penguin Publishing’s crime fiction series. In researching this series, I discovered an obscure radio adaptation of Woodthorpe’s novel, produced by the BBC in 1963 under the title Storm Over Polchester. I’m including a link to a recording of that production in the show notes. In 1969, the BBC released a television adaptation of the story starring Cyril Luckham and John Nettleton, as part of its popular anthology series Detective. Unfortunately, there is no copy of this episode in the BBC archive. Despite these adaptations, the world eventually forgot about The Public School Murder. Today, copies are nearly impossible to find—at least in English. The most readily available version is a 2015 reprint of a Spanish translation of the novel— titled Una bala para el señor Thorold (“A Bullet for Mr. Thorold”).

After writing seven more detective novels, R.C. Woodthorpe retired as a novelist, returning to journalism and reinventing himself as a competitive chess player. Single most of his life, in 1954 he married Daisy Mansell. The couple lived together until Woodthorpe’s death in 1971. Though extremely popular in the 1930s and 40s, all of Woodthorpe’s novels are out of print; the author himself is so forgotten that it took serious archival research to piece together the outlines of his life. With any luck, this podcast might help reverse this trend.

Though forever marked by the violent death of Elliott Speer, the Northfield Schools honored the memory of the visionary young headmaster by growing in size and national importance. The Northfield Seminary for Girls boasted several prominent alumnae, especially in the arts. Former attendees include: Bette Davis, Natalie Cole, Uma Thurman, and Laura Linney. The Mount Hermon School for Boys continued to strive for educational excellence, graduating several prominent politicians, CEOs, artists, and intellectuals. Its former students include American essayist John D’Agata, actor Misha Collins, and literary theorist Edward Said.

In 1971 the two schools merged, becoming the “Northfield Mount Hermon School.” Today, Northfield Mount Hermon is a secular, co-educational institution. Its beautiful campus was recently featured in Alexander Payne’s wonderful 2023 film The Holdovers. Those visiting the school today can still see Ford Cottage, where Elliott Speer’s life was cut short nearly ninety-one years ago. Visitors claim that the pockmarks from the buckshot that killed Elliott continue to mark the wall of his former study. As you walk from the headmaster’s residence toward West Hall, you might also notice a granite monument, erected in Elliott’s memory. It bears an inscription that reads in part, “He invigorated Mount Hermon by enlivening the academic and social life of the school and by introducing interscholastic athletics. He was always an inspiring presence to students in his office, in his home, and on the campus.” This memorial stands as a tribute to the values he kindled in his students during his brief tenure as headmaster and as a reminder to present and future students of the legacy of Elliott Speer.”

Next time, in our fifth and final episode, we will think about some of the unresolved questions raised by the Mount Hermon mystery, including the most troubling one of all: Did Thomas Elder actually commit the crime? And, if so, how did he get away with it?

Comments